A Journey Through Modern History: Berlin, Munich, and Krakow

Some reflections on beauty, terror, and the philosophy of law.

Germany has always been a gap in my travel experience. In fact, as much as I felt I had learned through books and school about its all too recent Nazi and Soviet past, now that I have visited, I realise that this has never been quite enough to put the pieces in place. Much like many of the other countries I have visited, I have concluded that it’s important to actually physically visit the place to get a better sense of the gravity of what has transpired.

The moment I arrived in Berlin, I felt an infectious energy. Despite its past, it is now an extremely lively, functional, and creative city. But walking the streets, I was shocked by just how much grim history took place on every corner. The city has become like an open air museum to terror, extremism, and the crumbling of democracy.

I was in Berlin to take a Philosophy of Law unit, which was hosted at Humboldt University. The University itself is significant to World War II history, as the Law School is one of the most famous locations where the Nazis burned books (about 20,000 went up in flames at this location on 10 May 1933).

At the site in Bebelplatz, there is a hole in the ground that is home to a permanent art installation by Israeli artist Micha Ullman. It contains a scarcely visible bookshelf, which is forever empty. Written on a plaque is the following quote, which was authored by a 19th Century writer, well before WWII:

“Where they burn books, they will in the end burn people.” — Heinrich Heine.

We learned about famous students and professors at Humboldt who were forced to emigrate due to the Holocaust, such as Albert Einstein. There are gold plaques in the pavement surrounding the university that share the names of academics, professors, and students who attended the university and were deported and killed in German concentration camps.

I was staying near Checkpoint Charlie, an area which has now become a tourist attraction in itself. Even this feels odd to see tourists smiling for pictures in front of it, as a reminder of the former border crossing between West and East Berlin, when just over 30 years ago people were being shot to their deaths at that same location, simply for trying to escape.

Even outside of the city, the past was impossible to ignore. One day, I went with a group of classmates from the course to a lake near Berlin to go for an evening swim. The wind, clouds, and rain quickly picked up, and we shivered our way towards the water anyway (as Australians, we were determined to swim). The water was warm, and the rain eventually cleared, making way for a dramatic sunset of red, orange, and purple. When we were in the water, one of my friends turned to me and said,

“See that mansion on that island over there? That’s where the the Wannsee Conference was held, that famous Nazi meeting where the execution plan of the Final Solution was agreed upon.” This was a meeting that took only 90 minutes, that even Hitler didn’t attend.

All of a sudden the dark weather took on a different, sinister meaning. I thought that this history must be in the shadow of everything that happened in modern Germany.

Legal Protections on Democracy in Germany

We were to learn more about the shadow of this history in class. Amongst debating insightful philosophers’ theories about the law’s role in liberty, human rights, civil disobedience, and justice, we were very lucky to have two guest lecturers from Humboldt University talk to us about the German legal system post-war, and the strict measures in place to protect its young democracy.

Joseph Goebbels, who was head of the media during the Nazi Regime, famously said, “It will always remain one of democracy's best jokes that it provided its deadly enemies with the means by which it was destroyed.” Germany’s post-war constitution and judicial system is very much set up with this risk in mind, containing strict protections on democracy.

The German Basic Law (Germany’s current constitution) now protects human rights, with ‘human dignity’ being the number one most important right that could ‘trump’ any other, particularly concerning any infringements by the state. This is contained in Article 1 of the Basic Law:

“Human dignity shall be inviolable. To respect and protect it shall be the duty of all state authority.”

Other rights that are explicitly protected in the constitution include (but are not limited to) personal freedoms, equality before the law, freedom of expression, freedom of assembly, and freedom of movement.

On the contrary, there are somewhat stricter laws that restrict some human rights, such as that protected right to freedom of expression in the famous prohibition of Holocaust denial in Germany. Extremism and radicalisation is taken extremely seriously in Germany, and there are several protections to stamp this out before it can take flight. This is a live topic with extreme-right party Alternatives for Germany gaining momentum, and a recent court ruling that it is a ‘suspected extremist party’ (which could prevent it from running in future).

The Federal Constitutional Court is Germany’s most venerated and trusted government institution, seen as the guardian of democratic values. This is partly due to the structure and judicial process of the court. For instance, judges are appointed to the court by the Parliament and a legislative body that represents the sixteen state governments on the federal level, and the election of a judge requires a two-thirds vote — meaning that all political parties must be in some level of agreement on each candidate.

On the matter of decision-making, the judges of the court must come to a unanimous decision on all cases — quite different from many other jurisdictions (such as Australia) that allow for dissenting judgements, which are also published. There are no major checks and balances on the court’s decisions, rendering it quite powerful for a government organisation. However, the public sentiment keeps it somewhat accountable, and the structure and judge selection process are also seen as powerful restraints.

The Reichstag building is one of the most famous buildings in Berlin to this day, known for both its dark history and the new dome on top of the building, which symbolically allows the public to look into Parliament.

It is curious that the Australian Constitution does not contain such explicit protection of as many human rights as the German Basic Law and other modern constitutions, though (uniquely) we are a country that has never suffered under a fascist or communist regime. Upon recently reading Paul Lynch’s book Prophet Song, I was reminded that this doesn’t mean that we should become complacent, because democracy can disintegrate quickly. Events like the outbreak of COVID-19 and regulations infringing on personal liberty to balance the protection of others should be scrutinised and questioned. My key reflection from the Philosophy of Law course was that we must not be complacent about the protection of democratic values, even in a country with a seemingly stable democracy.

Sightseeing Highlights of Germany and Poland

Berlin

Berlin is a complete construction site at the moment — with renovations happening across major buildings like those in the Gendarmenmarkt, the Pergamon Museum, which is currently closed for 14 years (so I guess I’ll see it in 2037?), and parts of the Tiergarten. While I couldn’t find any evidence of one specific unified building project happening, there has been a push to rebuild and restore Berlin since the end of World War II and the fall of the Berlin Wall, so I imagine these accelerated construction efforts form part of this.

I found the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe in Berlin a very powerful and moving art installation, which is designed to be interpreted in many, many different ways. The dark, heavy columns for me evoked grave stones and bar graphs, lifting and sinking at the sheer number of people who had died cruelly and needlessly at the hands of the Nazis.

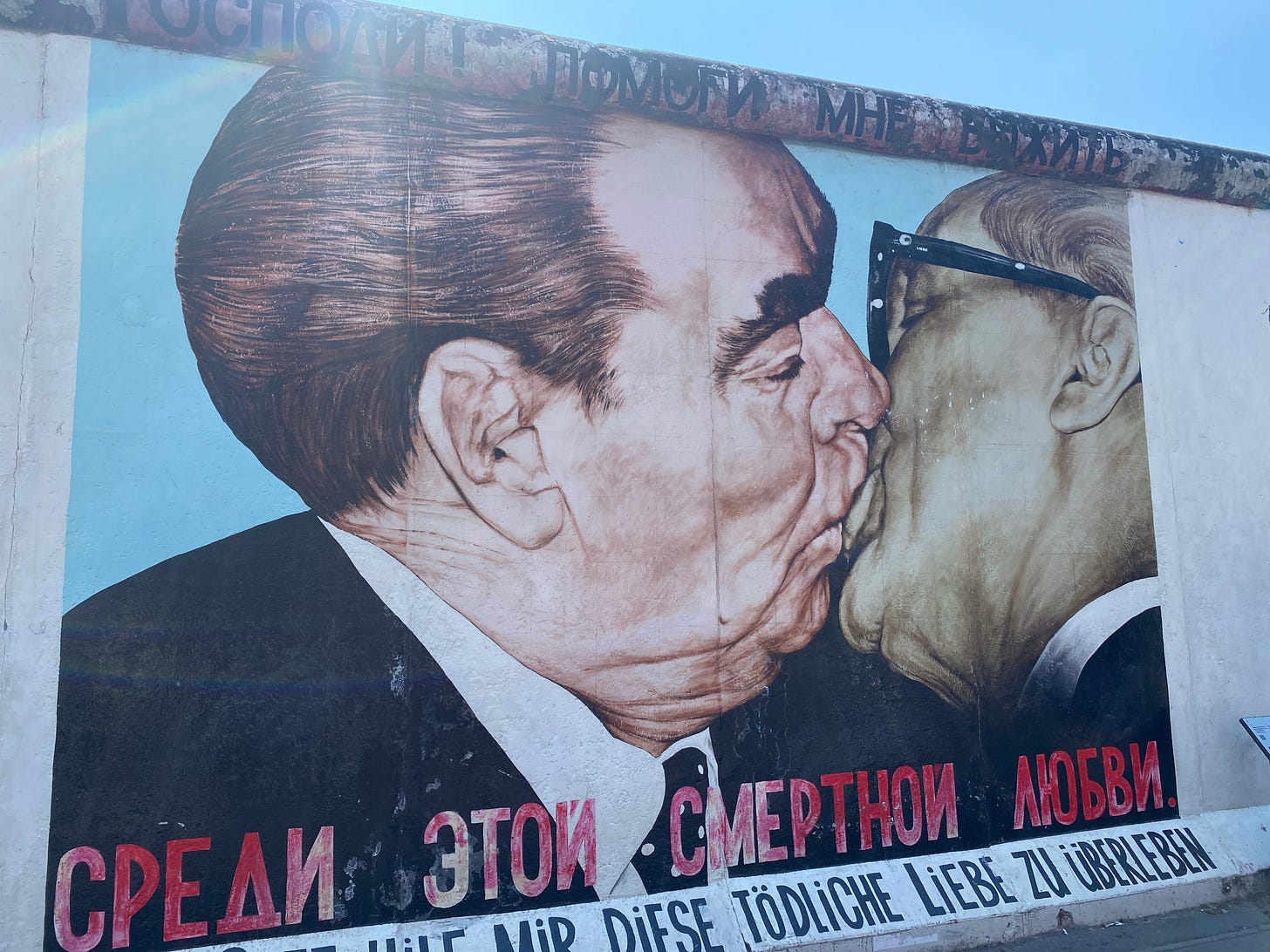

The East Side Gallery was also an iconic memorial to the Berlin Wall. Even though the beautiful, brightly coloured art evoked hope and renewal, I couldn’t remove the monument from the feelings of shock about the inhumanity and absurdity of the wall that kept so many people barred from freedom.

I was also horrified visiting the Topography of Terrors at just how many people were actively involved in orchestrating the ‘Final Solution’. It was completely unbelievable to me that such a large number of people could be capable of such evil (and not only from a position of self-preservation, but a position of actively believing and acting on such horrible ideals). This was only accentuated by learning more about the Wannsee Conference, which as I mentioned earlier, Hitler was not even present for.

On a lighter note, the Berlin nightlife was also good fun. I’ve never really experienced clubs where security turns you away for not dressing ‘cool’ enough, but I guess at 32 there is still a first time for everything. (Let the record show that I was let in). We also went to some trendy outdoor bars where people weren’t allowed to take photos, to avoid the ‘tourist’ factor.

I thoroughly enjoyed the Mauerpark Flea Market as well, which had great quality market stalls and locally made fashion. I managed to pick myself up a little Berlin souvenir from there!

My overall take on Berlin was that it is a city that I very much wish to return to. There are many galleries, museums and art installations that I didn’t have time to visit, so I have no doubt I’ll be back! But despite it all, I found the shadow of such recent, horrible history quite eerie, and wondered if it would hang over the city forever.

Munich

If I thought that Berlin was a functional, clean, and spacious city, arriving in Munich made Berlin look like it was struggling. Money dripped from very street corner, painted façade, and boutique window. Women walked down the streets with gold, diamond, and pearl jewellery, and carried designer bags with such elegance. It was the kind of money that screams money, without saying a word.

It struck me that Munich was a city full of economy, opportunity, and a luxurious lifestyle, with its lush green parks, wide streets, and palaces full of art. On a hot Saturday, people flocked to the Englischer Garten and literally let the rapid river current carry them down, while surfers tackled the waves at Eisbachwelle. The mountains were a short train ride away, as well as the spectacular cycling green of the Bavarian countryside. Heck, you could even watch the Taylor Swift concert from a manmade mound that looked out onto the stadium!

It was some kind of utopia for people with money. Yet even in this place, the dark history was impossible to escape.

In one of the main squares (Odeonsplatz), a monument remarkably similar to the Loggia dei Lanzi in Florence, once contained a Nazi memorial to German soldiers killed by their political enemies. If citizens of the Reich did not stop to do the Nazi salute in front of it, they could be shot in one of the backstreets (there is now an art installation as a memorial to those who were killed there).

In one of the Bavarian beer halls (Bürgerbräukeller), a putsch was famously staged by Hitler to overthrow the government in 1923. Hitler was jailed, where he wrote Mein Kampf, and it was this experience which made him realise that his rise to power would take place most easily through the path of legality. The rise happened slowly but surely in the years following his release in 1924 by strategically disseminating more about his ideas through book publication and campaigning to grow membership of the Nazi Party. Of course, the party did gain power and nominated Hitler as its chancellor in 1933.

I learned a bit about the birth of the Nazi Party in Bavaria in the NS-Dokumentationszentrum museum, which provided a detailed history of the stages of their rise to power. I was moved by a modern artwork I saw there. Mentsh has many meanings in English: ‘person’, ‘person of integrity and honour’, and the artwork makes specific reference to Article 1 of the German Basic Law.

I was impressed that Germany seemed to keep all these museums as free entry (as they should be), in order to remove any hinderance to educating the public about the darker parts of its history.

Bavaria is still to this day one of the most conservative regions of Germany, with the Christian Social Union winning every election of the state parliament there since 1946.

Krakow

I was very lucky to explore Krakow with my friend Julia, who I met in Perugia while studying Italian! She took me on an immersive tour of the Polish cuisine and culture, and is probably responsible for me gaining at least 5kg in the 3 days we were there.

I found Krakow to be a very elegant, romantic and regal city, with beautiful parks, grand buildings and squares. It was simply a pleasure just to walk around the city, and enjoy its many fantastic galleries and museums.

I particularly enjoyed visiting the Krakow National Museum, which was free entry the day we went, and housed a very interesting collection of Polish art from the late 19th Century to post-war period. The collection painted a bleak picture of the weather, conditions, and lifestyle particularly in the lead up to and post war with some very beautiful and distinct artworks.

The Czartoryski Museum was also definitely worth a look, which houses a da Vinci painting (Lady with an Ermine) and is set in an extraordinary building. However, this museum was very expensive by Polish standards (probably because of the da Vinci), so I would recommend going on a Tuesday, when it is free entry!

We also took a stroll through the Jagiellonian University’s Botanical Gardens, which we had low expectations for, but ended up being an extremely large, beautiful, and colourful gardens with so much plant variety!

One of the most curious things about Krakow that I noticed, is the existence of a ridiculous looking mascot which resembles a wizard on a horse, that appears on public transport, brand names, and buildings all over the city. His name is Lajkonik, and is an unofficial mascot of the city. There’s even an annual festival where people dress up as him (the Lajkonik Festival), which has occurred for 700 years. The origin of this mascot is disputed, however apparently it relates to the Mongol invasion of Poland in the 13th century, where the Polish victors stole the Tatar Khan leader’s clothing and rode triumphantly on a horse through the city.

A moment for the Polish food…

There were lots of food highlights. I’m not going to lie, I had low expectations for Polish food and had a preconception that it would be very bland.

Julia made sure that I knew that Poland was most famous for its soups — so we were sure to try one before every meal (even if this left us rolling home afterwards!). My favourite was a thin beetroot soup that had meat dumplings inside — surprisingly delicious!

Then of course, we tried pierogi, the Polish variation of dumplings. I loved how packed in they put the meat, especially with lots of pepper. It made for a filling meal and interesting flavour and texture.

I also enjoyed little cabbage packages with mushrooms and meat inside (gołąbki), which were very juicy and delicious!

However the one food to top them all was the blueberry bun we stopped for one very hot day. The blueberries were so fresh, so dribble-y, and so delicious, which was only accentuated by the soft and dewy bun. Honestly, it was one of the best things I ate on the trip, and I regretted getting only one to share between us! (The place I had this was Bun Bakery — I am led to believe that they create seasonal buns at different times of year depending on what foods are in season, so is well worth a visit!)

Overall, I was surprised by just how flavourful the Polish food was. (Despite surviving a communist regime, German occupation during war times, and poverty).

The dark history of Poland

Despite all the beautiful streets, squares, and buildings, Poland too has a dark past that can’t be ignored. During the German Nazi occupation, some of the most treacherous persecution of the Jews occurred, who made up over 3.3 million of Poland’s population in 1939. By the end of 1945, only an estimated 240,000 Jewish people were residing in Poland, and Poland had lost almost one fifth of its total population.

We took a walking tour about the Jewish community and culture in Poland pre- and post-war, and it was interesting to hear about the shifting use in religious buildings, the inhumane conditions of the Krakow ghetto, and the part of some of the locals (such as Tadeusz Pankiewicz, The Pharmacist) in rescuing and protecting Jewish people from persecution.

We also took a day tour to Auschwitz I and II on one of our days in Krakow, and we were truly shaken by what we saw. I am not going to go into many details, because the whole day sickened me to the core. It was possibly the most evil place I have ever laid eyes upon.

Again, the sheer scale of this evil was astounding. I was once again taken aback by just how many people were actively involved in orchestrating The Final Solution, and who had bought into this ideology. Perhaps most hypocritical of all was seeing evidence that the Nazis had burned one of the main crematoriums in an attempt to destroy the evidence before Soviet troops arrived to liberate the camp. This to me spoke to a clear consciousness that what they had done was unspeakably evil and would warrant punishment, yet even this was not enough to stop them from carrying out these horrific acts.

My takeaway from this place was that humans are capable of such an intense level of evil (something we are even seeing right now in some parts of the world), and that we all have a responsibility to stand up for each other and defend human dignity. Our guide left us with some powerful words from German theologian Martin Niemöller:

“First they came for the Communists, And I did not speak out, Because I was not a Communist.

Then they came for the Socialists, And I did not speak out, Because I was not a Socialist.

Then they came for the trade unionists, And I did not speak out, Because I was not a trade unionist.

Then they came for the Jews, And I did not speak out, Because I was not a Jew.

Then they came for me. And there was no one left, To speak out for me.”

Reads on the Road

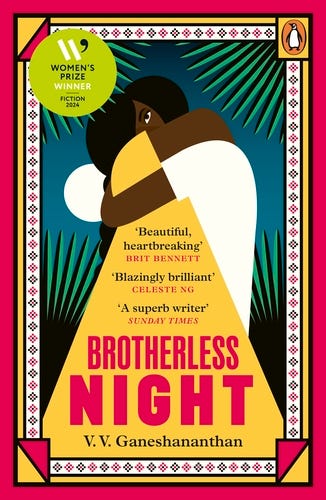

Brotherless Night by V.V. Ganeshananthan

I read this book as pre-reading for my upcoming trip to Sri Lanka. Like many mainstream Sri Lankan novels, it concerns the civil war and rise of the Tamil Tigers. It also won the Women’s Prize for Fiction in 2024. The story centres around the main character, Sashi, who dreams of becoming a doctor just as the war is breaking out, and the impact of the loss of her male friends and brothers (who become swept up in the rise of the Tigers) on those who are left behind. The book was very tenderly written, and covers very intense subject matter in a sensitive manner. I often struggle to connect with main characters such as Sashi who don’t really seem to have many flaws (eg. she was the most capable doctor, the one willing to stand up when others won’t, etc, etc). However this did not detract much from the brilliant story that was told.

Thanks for reading Reads on the Road! I am currently on a flight back home for a friend’s wedding before heading off to Sri Lanka. In my next newsletter, I’ll share some tips from my recent hiking travels to the Dolomites in Italy! Ciao!

Erin, I look forward to reading your reads on the road.So much history written in your words that I can understand. You write like we are walking and experiencing it all with you.

My favourite Reads on the road yet! Fascinating exploration of things that in past I have walked on by…..I look forward to the Australian edition😊.