Which Region of France Gets More Rain, Normandy or Brittany?

Well, that depends on who you ask.

Standing at the top of the Mont St-Michel, that grand 8th century abbey that still stands proudly with its distinctive silhouette on the Bay, our tour guide points out to the river.

“See there? The Couesnon River is a natural frontier between Normandy and Brittany.”

He explains that there is a fierce debate that has raged on for centuries: who owns the Mont-St-Michel?

Pointing out again, he says:

“But look. The Mont-St-Michel clearly sits to the left of the river, in Normandy. Notice how you look to the right of the river at Brittany, and it just looks shit?”

We look out and laugh — there is no difference. The sky seems gloomy whether you look left or right. Thankfully, we only need to wait 5 minutes for this to change, as the sun would inevitably come out, before disappearing once again.

As local legend has it, in 708 AD the bishop Aubert (a Norman) conceived of an extraordinary idea in his sleep — to build an abbey dedicated to Saint Michel on top of the rock in the Bay. It has been through multiple reconstructions over the centuries, and Brittany owned it for a short period from 867 AD, when it was conceded to the Duchy of Brittany as part of the Treaty of Compiègne. However, the land was eventually handed back to the Normans when the duke of Normandy at the time (William Longsword) annexed the land in 933 AD. It has remained in Normandy ever since.

Later, we travelled to Cancale, a small seaside town in Brittany, where we saw the Mont-St-Michel from a different angle on the Bay — this time with some glorious sun.

Sitting down with some fresh oysters that Louis XIV himself used to transport to the Palace of Versailles, we looked out over the glittering water at the abbey’s silhouette on the horizon. The day could not have been more perfect.

Mum asked a man at the coffee cart, “Is there ever a time when you can’t see the Mont-St-Michel?”

The man looked us dead in the eyes with a straight face, and said:

“Well, that depends on the rain in Normandy.”

It seems the French have a long memory.

—

I have travelled fairly extensively in France over the years. So when I was researching which regions to travel to next, Normandy and Brittany were fairly obvious choices.

Firstly, because I had never been to either before (besides a quick stop at Monet’s Gardens in Giverny, which is technically in Normandy). And secondly, because of the different angles on history they offered — Normandy for its significance in medieval and World War II history, Brittany for its neolithic history. I had also heard that the coastlines of both regions were rather beautiful.

But that’s about all I knew.

I did not know about the fierce rivalry between Normandy and Brittany, seemingly close neighbours. This dynamic apparently goes back as far as the Breton-Norman war from 1064-1066, which even features in the Bayeux Tapestry. Today, it covers everything from who makes the best crêpe, who makes the best cider, and whether or not butter is better salted or unsalted.

Despite this now friendly rivalry, locals from both regions (when pressed) will admit that the other region has a lot to offer. So, here’s what I learned from my travels through these two fascinating regions.

Normandy

Hope, Symbolism, and Storytelling

We know that the winners of wars tell history. This was something I reflected deeply on in Normandy.

The Bayeux Tapestry is one such example of this. The tapestry tells the story of the Battle of Hastings from 1066 on a 68-metre-long linen cloth, embroidered with vivid storyboard scenes of the events leading up to, during, and after the Norman victory over England.

Historians say it was likely a work of propaganda designed to educate the mostly illiterate population, changing details and presenting the story of the Battle of Hastings in such a way as to truly change King William I’s reputation from that of a Bastard to a Conquerer once and for all. (Surely one of the most brilliant executions of a rebrand of all time!)

Then of course, there is the World War II history of the Normandy Landings.

Standing on Omaha Beach, our tour guide painted us a picture of bodies covering the hard pebbles in blood, as the Germans shot the American troops to death (and vice versa). But now the ocean laps at the shores, solemnly and gently, as if it too is aware of what it has seen.

A beautiful sculpture called ‘Les Braves’ reaches up towards the sky, with sails representing hope, brotherhood, and youth rising. The work was created by French artist Anilore Banon, and was supposed to be a temporary installation for the 60th Anniversary of the Normandy Landings in 2004 — however residents were so moved by the work that they petitioned for it to stay.

I was stunned by the passion our British tour guide had for telling the D-Day Landing stories from multiple sides and sources, a matter he considered of grave importance.

He told us stories of the human side of the war — of teenage German soldiers cohabitating with French villagers, and old French ladies who had survived the war looking back on this time now and wishing the German boys well. Of the horrific bunker conditions the Germans were staking out in at Pointe du Hoc. Of the disasters in the building of the Atlantic Wall, and the failures in German conscription that partly led to their defeat. (Their army in Normandy was mostly made up of the elderly, teenage boys from the Hitler Youth, and prisoners of war).

We learned about the path of destruction the Americans left in their wake during the Liberation, of towns like Caen and Saint Malo, which were 70-80% destroyed by bombs and left in ashes. Bayeux is called “The Town of Miracles” because it was somehow left unharmed, but there are nearby towns that have not yet forgotten the pain and destruction that was inflicted by the Americans — even if for a higher cause.

“There are no winners in war,” our guide repeated.

--

I have always been particularly fascinated by the story of Joan of Arc, which is why we paid a visit to Rouen, the capital of the Normandy region and the town where she famously faced trial for heresy and was burnt at the stake.

How did a girl of not even 19 years old manage to garner such an epic status in the history of France, with only 2 years between when she first presented herself to the Dauphin Charles VII with tales of her visions, and her brutal death in 1431? You’d surely need to do at least a thesis worth of research to answer that question properly. She has stood strong as a symbol of hope, faith, and goodness in France, prevailing throughout the centuries.

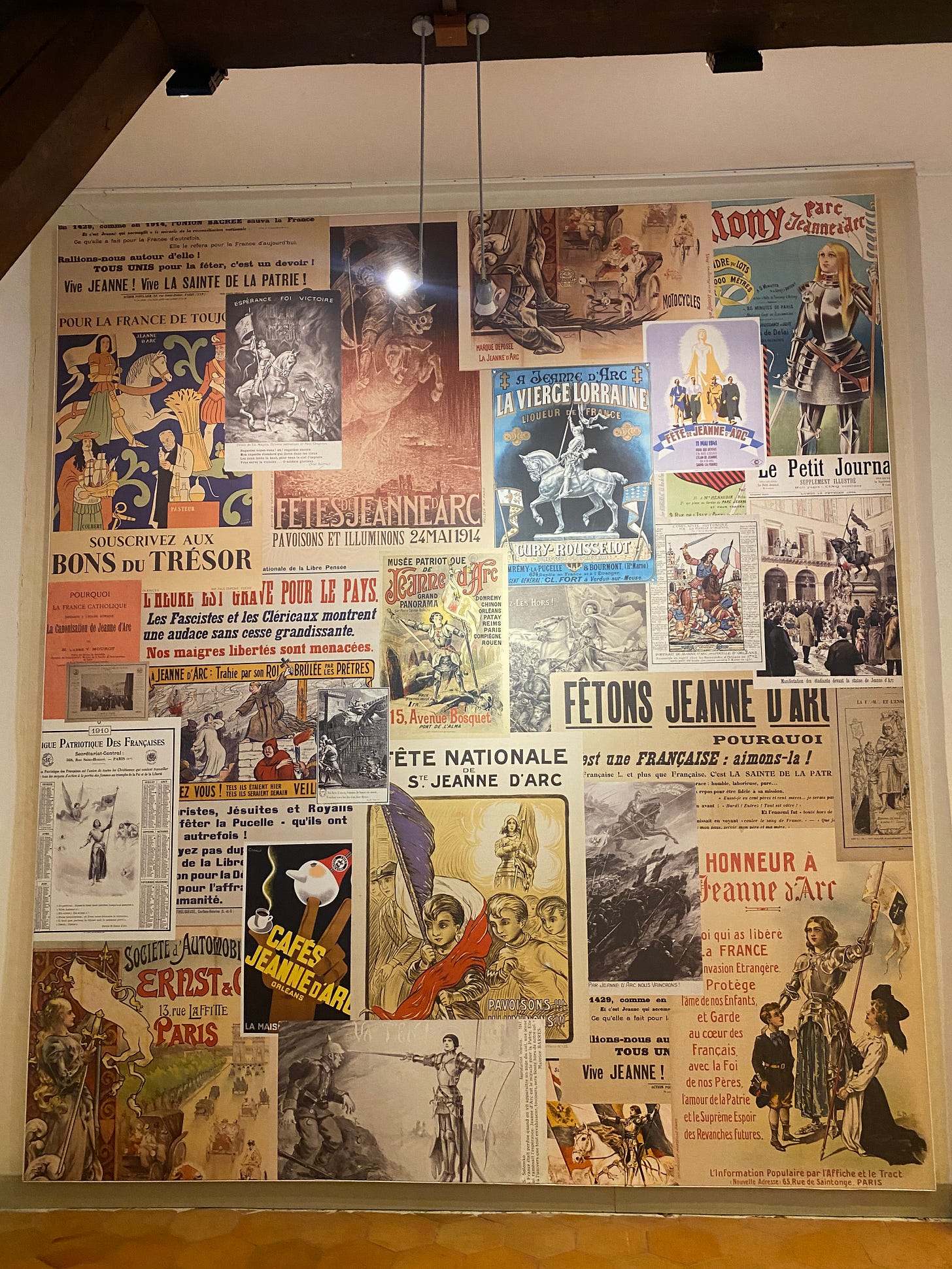

We visited the Jeanne d’Arc Historial to learn more about the trial, and there were several key recurring themes from history that stood out to me.

Joan of Arc was a virgin, young, pious… can you draw any parallels with other deified women in history here? Her story also embodied hope for the French people who were suffering at the hands of the English, losing their territory and identity. Perhaps it took believing in a higher power and purpose for them to take the risks and muster the motivation required to defeat the English and reclaim their land.

However, interestingly, the moment this young woman’s piety was doubted, the moment her integrity was questioned, despite all she had already done for France, she was quickly sent to her death. And of course, just months after her death, her remaining visions came true, and the English were defeated.

Her convictions were later overturned in a retrial (by which time, she was already long dead). So by the end of it, all I could think about was what an unbelievable waste and theft of human life this whole sorry tale was.

However Joan’s image and legacy lives on. She has since been used in different campaigns and stories in history, such as the French Revolution, World War II and modern pop culture. She was officially Sainted by the Catholic Church in 1920.

It was very interesting to visit the beautiful medieval streets where she met her end and reflect on why and how her story has resonated and endured for so long.

Side note: I’ve been doing some reading about the death penalty in France (which was only abolished in 1981), and it’s quite extraordinary how callous the regard for human life was in such a Catholic society, even up until recent times. This brutality is something that Victor Hugo advocates quite strongly against in his book I recently read, Le Dernier Jour d’un Condamné.

Natural and Man-Made Beauty

One of my favourite things about France as a country is the pure variety of landscapes, scenery, and architecture you can find in every different corner of the country. Normandy has its own unique flavour, feeling almost English in parts of it (which probably makes sense, given its position on the La Manche (what the French call the English Channel), and Norman history). But there were some sights in particular that left their mark on me.

The Rouen Notre-Dame cathedral was something to behold, a source of inspiration for Monet in the 19th century, who painted a famous series that now hangs in the Musée d’Orsay and the Musée de l’Orangerie in Paris. It is quite an impressionable building, casting its shadow on the main square of Rouen. Weaving between the old, wood-panelled streets, you can discover other beautiful cathedrals like the St. Maclou Catholic Church and the Saint-Ouen Abbey, just moments from each other.

Monet also found inspiration at the limestone cliffs of Etrétat, one of the most beautiful places I have ever visited in France. It was incredible to climb up and see the powerful view across the ocean, with the impressive cliffs carving shapes on the horizon, combined with the quaint architecture of the small, seaside town. Though the beach was full of hard pebbles that made a stroll along the shore a somewhat less pleasant experience than the white sands of Australian beaches, it was so peaceful to sit by the ocean in the sun and have a coffee or a wine en terrasse.

I also found our visit to the Mont-St-Michel somewhat mythical. It is extraordinary to think that people lived within its walls, particularly when we felt the enormous winds blowing in from the English Channel. There is something particularly romantic about the idea of someone having a vision and bringing such a masterpiece to reality.

However, on the flip side of these beautiful stops, cycling past the Seine on our way to a charming village called La Bouille, we were shocked by how much of the ride was tainted by the sight (and smell) of gigantic factories bordering the river, casting their shadows on the beautiful neighbouring historic towns.

The impact of humans is everywhere.

Brittany

Sunshine on the Emerald Coast

After almost a week of constant rain and overcast days in Normandy, somehow we got lucky and saw the Emerald Coast of Brittany in its full glory with some excellent sunny days.*

We began by exploring the stunning walled city of Saint Malo, where we walked across beautiful ramparts for some epic views of the coastline and surrounding beaches. We also tasted the local speciality — crêpes made from black wheat, a special kind of Breton buckwheat. The sheer force of the wind and cold made it difficult to imagine swimming in the beautiful beaches and ocean pools at any point — but I’m sure in summer this would be an absolutely idyllic place.

Nearby, the holiday town of Dinard was also exceptionally beautiful (and provided an epic view of Saint Malo from across the water!)

But one of the biggest highlights was taking a bus to Cancale to taste the famous oysters, soak in the ocean views, see Mont St-Michel from across the Bay, and also hike the Sentier des Douaniers (or at least, a section of it!). You can certainly see from this angle why the area is called the Emerald Coast, as the water sparkles a beautiful green-blue.

The Breton Identity

In one shop in a seaside town called Concarneau, I had an interesting interaction, which remained a common thread throughout my travels in Brittany:

“Mais tu parles bien français! J’ai jamais vu un australien qui parle aussi bien français.”

“C’est gentil! Les Parisiens ne le disent pas. Je trouve que les gens ici sont vraiment plus sympa.”

“Oui, mais les Parisiens ne sont pas des vrais français. En Bretagne on s’est habitué à travailler dur!”

This woman was surely just flattering me in the hope that I would buy something from her shop (I did). And I was a bit puzzled about why she though Parisians didn’t work hard… But she raised an interesting point. What was it about the Bretons that was so different? And why did they feel almost like a different country to the rest of France?

It wasn’t until my very last stop in Rennes that the pieces started to fall into place for me about the Breton identity.

Rennes is home to an extremely good (free) museum about the history of Brittany called the Musée de Bretagne, which explains the stories of the humans that have lived on the peninsula from about 500,000 BC to the present day. I felt like I was reading the book Sapiens, but specifically about Brittany. Truly incredible longevity and history there, with constant periods of change.

The visit through the museum traces humans from prehistory, the neolithic period, the bronze age, iron age, Roman takeover, early Christianity, medieval times, post-French Revolution, and World War II, right up to today. The modern-day Bretons came over from England in the 7th and 8th centuries, after their hometowns of Cornwall and Devon were under threat of constant attack from Vikings and Irish pirates. In fact, two regions of Brittany today are still named after these places (Cornouaille and Domnonée).

Independence is still a sensitive topic in Brittany. The region was once a Kingdom, but became a Duchy in 939 following several Norse invasions and a negotiation with the King of France. It was later integrated as a department of France after one Duke (Francis II) failed to produce male heirs, and his daughter Anne of Brittany became the Duchess of Brittany. Having a female heir put the autonomy of Brittany under threat — and she eventually married the King of France, so Brittany became incorporated into the Kingdom of France shortly after her death, in 1532.

There was further change after the French Revolution, when Brittany got subdivided into 5 departments and unified as part of France, which made retaining their languages and culture significantly more difficult.

Their traditional Celtic language has now almost entirely disappeared (only 210,000 native speakers of Breton exist today in Brittany, declining from over 1 million speakers in the 1950s). Some Eastern Bretons also speak Gallo, a romance language originating from Maine and Normandy (today less than 190,000 native speakers remain).

However, there has been a recent resurgence and interest in keeping their unique dance traditions alive through the annual fest-noz and fest-deiz (which I was lucky enough to see in Vannes!).

And one final fun fact I learned — in the later 19th and early 20th centuries, you could tell which region a Breton woman was from simply by the style of her headdress!

Village Life in Brittany

Brittany boasts hundreds of charming small villages within an easy distance from the larger towns by bus, car, or train. Many of the villages and small cities I visited were fortified, which gave a sense of the former grandeur of the Duchy of Brittany, and the constant threat of attack in this region.

Every village had something unique and interesting to offer. We had a beautiful day out in Dinan, which used to be quite an important town in the Duchy, and home to the Château de Dinan, one of the oldest castles in the region. Quimper also has an interesting history of faïsance, which was an important trade during the 17th - 19th centuries. I thoroughly enjoyed my visit to seaside town Concarneau, which had a large maritime working culture and beautiful walled town with irresistible boutiques.

However, one of my favourite stops in Brittany was to the small village of Pont-Aven, which sits in the southern region of Cornouaille. This village was home to a school of Impressionist artists started by Paul Gauguin, who created a sub-movement called synthesism dedicated to evoking emotions and colour in the idea of a landscape, rather than depicting realistic detail. A fellow artist recommended that Gauguin live in this village due to the cheap rents and beautiful landscape.

As I strolled through the Bois d’Amour, I could easily see how artists might find inspiration on the banks of the river and shade of the woods here. The streets of the village were also so charming, and there is a beautiful Musée de Beaux-Arts to pay homage to the town’s Impressionism roots.

To celebrate the 150th anniversary of Impressionism, there was a special exhibition on one of the few (recognised) female Impressionist artists, Anna Boch. Visiting this exhibition was easily one of the highlights of my time in Pont-Aven, and in Brittany. Anna Boch was a true trailblazer in the movement, part of Les XX, a respected group of Impressionist artists in Belgium. She was famously one of the only people to purchase a Van Gogh painting during his lifetime (clearly a woman of progressive taste).

I loved the way that she depicted Breton landscapes and women in her own paintings, capturing poignant moments of daily life as they worked in fields, washed clothes, and caught fish.

Perhaps this is the Breton work ethic the lady in Concarneau was describing.

Reads on the Road

Bird by Bird by Anne Lamott

This book is frequently recommended by influential writers as one of the best books to read about creative writing. I have read many books on this topic, with varying degrees of benefit. However, I must say that Anne Lamott does give some very handy, clever tips in this work that I have already introduced into my practice. She writes in a very genuine, personal, and funny way, weaving in her own anecdotes teaching writing, beautiful memories of her family, and stories of where she found her breakthroughs. I think the biggest takeaway I had from this book was about treating writing as a journey, not the destination, and most of all, a way of life. Very few people achieve vast professional heights through publication, so Lamott teaches people to stoke their passion and find fulfilment through writing using other yardsticks.

--

I have just spent a week in London to visit friends, have fun, and take a break from the language immersion, but now I have arrived in Perugia, Italy, ready to eat as much pasta as I can and learn Italian!

As always, thanks for reading, and feel free to connect with me on Goodreads :)

*PS: For those who want to know which region actually rains more, it’s about as tight a race as it could be. But it appears Brittany just wins — by a hair. (If you can call more rain winning).

The English expats must have felt right at home.

Fantastic read Erin. Super impressed by your passion and the breadth of your knowledge.

Fab and informative read Erin - a timeless recap of our journey together x