I had been reserving my eight precious remaining visa days in the Schengen Area (the European Union) for a triumphant return to Italy after my last epic stay. I couldn’t wait to get back amongst unbeatable bowls of pasta, their unique pride of place, and some plain old hospitality.

The best part? My partner was finally joining to get amongst the fun! (and to translate for me)

However, as we drove through the Veneto region and edged closer towards Trentino-South Tyrol, the landscape began to feel distinctly less ‘Italian’. Impressive mountains bordered the highway — enormous Alps with glacial lakes at their feet. The road signs displayed German and Italian instructions, though somehow the Italian word choice didn’t quite feel native. Cute mountain alberghi framed the streets, making the mountains feel somewhat closer in style to Switzerland or Austria.

If all this wasn’t enough of a clue that something was off, when we arrived at our hotel in Cortina d’Ampezzo, the welcome was cold. (Cold. In Italy!) My partner, who is Italo-Australian and speaks excellent Italian, offered to converse with everyone in their choice of Italian or English. If he started off in Italian, we got rudeness back. If we started in English, then anger, more rudeness, and a request to switch to Italian. There was no winning, unless you could speak German.

We have visited the North of Italy before. From Milano, to Lake Como, to Piemonte and the southern parts of the Veneto region, all of these places have (in our experience) still felt part of the national ‘Italian’ identity we know and love. Their regional influences on food, infrastructure, architecture, language and more actually contribute to the rich tapestry of the national identity. But the bitterness and rudeness we experienced in the Dolomites was unlike anything we’d experienced in other parts of Italy. It felt like something was deeply wrong, and seemed like a lot of fuss for people who were living in one of the most beautiful places in the world.

By the end of the stay we had devised a theory: this region has so much money coming into it from the rich Swiss, Austrian, and American tourists, that they didn’t really need us to be satisfied. They’d just get business from someone else.

However, as we started to dig deeper, the tension began to click further into place. The South Tyrol region, which includes much of the Dolomites, had been brokered as a deal between the Allies and Italy as part of the Treaty of London of 1915 during World War I, to coax Italy into joining the war. Essentially overnight in 1919, residents of the South Tyrol region had been told they were no longer Austrian, now Italian — and understandably, they weren’t happy about it. They went through further identity confusion during World War II, going through the fascist Italian regime (which banned the use of the German language), and subsequent Nazi Germany occupation.

In modern day Italy, the province enjoys a significant level of governing autonomy compared with other regions. But there is a small secession movement to try to absorb the South Tyrol region back into Austria.

Which begs the question: “If everyone is so dissatisfied, why isn’t there a bigger push for Italy to just hand the land back?”

When we asked an Austrian friend later, they did have one theory.

“Oh, the taxes are lower in Italy than Austria.”

Finally, something made sense.

What to know before heading to the Dolomites

The Dolomites is an enormous region. In fact, it’s not a region in itself — it incorporates three regions of Italy: Trentino-South Tyrol, Friuli-Venezia Giulia, and Veneto. So my number one piece of advice is, where possible, try to give yourself enough time to explore.

The way we tackled this was by booking a few nights’ accommodation on one side of the Dolomites (Cortina), and then the remaining nights on the other side of the Dolomites (near Bolzano). We then planned our hikes according to the side of the Alps we were staying in.

The Dolomites are also enormously expensive. With tourists coming in from neighbouring rich countries like Austria, Germany, and Switzerland, businesses can afford to charge a pretty penny. My advice would be to book accommodation well in advance, and budget accordingly for expensive meals, ski lifts, and transportation.

Highlights and Lowlights of the Dolomites

Politics aside, without a doubt, the Dolomites are home to some of the most beautiful scenery that I have ever laid eyes upon. Much like other parts of Italy, the land is so lush that it almost feels unfair to have so much beauty in one place. Every picture we took was like a postcard for the region.

Here are some of my favourite moments from our time there:

The pay-off at Tre Cime

In true Italian style, the process of getting to some of the hikes in the Alps was an absolute mess. The region is fairly poorly connected by public transport, so with everyone driving their own cars, parking was a nightmare. (More shuttle buses in National Parks is the hill I will die on!) After driving around for about 20 minutes to find something, and all the designated car parks full, we managed to broker a deal with a nearby hotel to park all day… at a price.

By the time we had walked over to the bus station, which would take us up to the trailhead, a chaotic line of frustrated tourists had formed. But if there’s anything I’ve learned about Italy from the last couple of years, it’s that somehow… chaos always works out. In the end, this line that would have surely taken several hours to budge in Australia took us all of 15 minutes to get through.

My partner and I were glad that we had not given up, because the Tre Cime di Lavaredo Loop was my favourite hike that we ended up doing. Not only was the trail fairly leisurely, but the views were extraordinary, and there was a nice refugio at the end to eat lunch.

Spectacular views at Seceda, past the crowds

We quickly discovered that the hiking culture in The Dolomites was… quite different to that of Australia. The European tourists seemed to take it a lot less seriously. It was not uncommon to see people bringing prams and young kids onto the rocky trails, wearing inappropriate shoes, and hanging out at the multiple refugi on the trail to settle in for an Aperol Spritz.

One of the more popular hikes in the region was Mount Seceda, which had a spectacular cliff face ideal for Instagram influencer photos. We were quite shocked to see lounge chairs at the top of the almost 15km hike, serving strudels and spritzes.

Interestingly, as soon as we started hiking down the hill, past the chair lift, all of a sudden the crowd disappeared and we were the only two on the trail. The scenery felt like Jurassic Park!

Safety first

The clash between Italian bureaucracy and German efficiency was at times comical. Many of the villages had extremely windy roads leading up steep cliffs, and as such, strict speed limits of 30km/hr had been introduced to enter the towns. In order to help the enforcement of this snail’s pace in a country of questionable drivers, they had installed speed cameras out the front of every village.

The only problem? They don’t work.

That’s right, the majority of speed cameras do not seem to record speed or report it to the authorities in this region.

But if you’re worried about how this might affect the enforcement of speed limits, don’t worry — they have a solid back up plan:

The food — a national disgrace

I never thought I would have a bad bowl of pasta in Italy. Or a limp pizza for that matter.

Not only did we find both of those things, but we found spaghetti bolognese with the sauce served on top of the pasta. We found pasta with cream in it. And in every food that would usually have enjoyed guanciale, prosciutto, or pancetta included, we found the dry and depressing substitute — speck.

It could be the worst region for food in Italy. And I’ve been to some tourist traps in Rome, and even handled airport food in Venice! Knowing the context and history of the region makes all of this make sense, but doesn’t excuse it.

Take for example, their other cardinal sin — bad coffee. Austria is a country that prides itself on their history of Viennese coffee houses, but the Austrian coffee brands they used, such as Julius Mein, just tasted stale.

We left in disbelief.

Reads on the Road

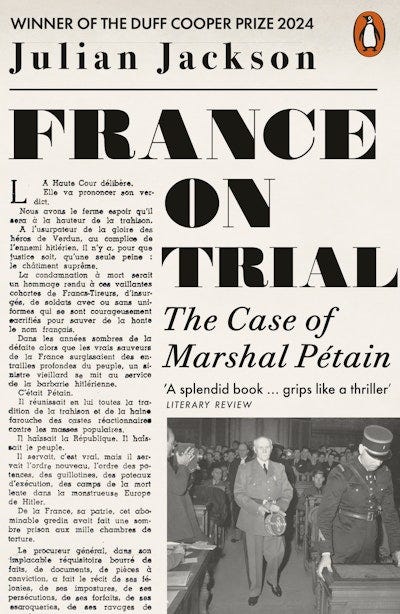

France on Trial: The Case of Marshal Pétain by Julian Jackson

Admittedly, this was not my first choice of book. I had run out of reading material once we left London, so borrowed one of my partner’s books to make it through. However it ended up being quite an interesting deep dive into the trial of Marshal Pétain, which I knew almost nothing about. It was particularly relevant to read following the time I spent in Germany and Poland. The book investigates France’s decision to enter an armistice with Nazi Germany, Pétain’s moral culpability in it all, and how his trial played out. It was very densely written, but covered many interesting perspectives, such as journalists, previous French politicians, large omissions from the trial, and how France has looked back on their history from a post-war lens. I was still left with many more questions, but my overall feeling was that the way France folded was a disgrace. Usually, these things come down to poor leadership. So I don’t exactly buy Pétain’s defence.

Thanks for reading Reads on the Road! I am now back in Australia after a two-week creative writing retreat in Sri Lanka, simply processing what has been an epic seven months of travel.

But the adventure’s not over yet. My next newsletter will be on the tumultuous time we spent in Albania. This destination has been highly trending, particularly amongst Australians, and somewhere that I just had to review. Stay tuned!

Me and Federico spent some time in Sud-Tyrol (Bolzano specifically) last year during our search for the perfect Italian home, and found the same as you! His rudimentary German got us further than Italian did. Excellent wine though! Ultimately happy we ended up in Perugia, and I hope you'll be back some day! 💕

I did not know this about the Dolomites!! How convenient about taxes!!